Gerald Reynolds of southern California raised this question in a comment posted to a podcast interview I conducted a few months ago with the fan website Rams Talk:

… The one thing I do know is one huge motivating factor for the Rams to move to LA in 1946 was the city of Cleveland leased out the only stadium in the city to the Browns of the AAFL [sic] and the Rams who had just won the NFL title didn’t have a place to play. How do you lockout a team that just brought a title to your city?

First, I’m glad and flattered Gerald took the time to listen in on the podcast and to comment. However, a tendency to “blame the victim” seems to strike nearly every city with the misfortune of losing a major-league sports franchise, including Gerald’s own Los Angeles.

Maybe I’m just a bit touchy on this subject. Like all native Greater Clevelanders, I watched Art Modell spirit the original Browns franchise out of Cleveland, then remain conspiratorially silent as many in the media and football fandom at large laid the blame for the move on a jilted region that had only supported the team for a half-century.

So … let’s look at a few facts from 1945 and 1946.

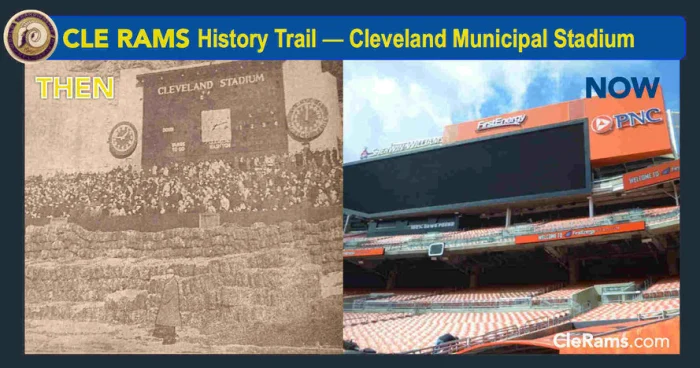

First, the Browns of the All-America Football Conference (AAFC) had no exclusive lock on Cleveland Municipal Stadium. Just like the L.A. Coliseum—which in 1946 became home to both the NFL’s Rams and the AAFC’s Dons—Cleveland Stadium was a taxpayer-owned facility. Baseball’s Indians shared it with the Browns for many years. The Rams could have used it too, if they had been interested.

Browns owner Arthur “Mickey” McBride was quoted in considerable detail on this topic. Here’s a passage from the Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 30, 1945 (which incidentally, was precisely two weeks before the media announced Rams owner Daniel F. Reeves was moving his team out of Cleveland):

“I’m even willing to share the Stadium with the Rams,” said McBride. “If they want to play down there on Sunday afternoon’s [sic] we’ll be glad to play our games on Friday nights.

“In fact, we’re arranging our schedule so that we’ll play most of our home games early in the season and finish up in the West and South. We don’t plan to play here in November or December unless we play the Rams.”

At League Park By Choice?

Were the Rams outmaneuvered by the Browns as the Stadium’s primary tenant? Sure. But they were not blocked out. By the end of 1945 the Rams hadn’t played their regular-season schedule in Cleveland Stadium for three years. Instead they had opted for League Park, the city’s other NFL-ready stadium. Rams general manager Charles “Chile” Walsh insisted the Rams were beholden to a lease at League Park. But in early 1945 he also had said that lease was for five years, and ten months later the Rams departed for L.A. So the lease may not have been as ironclad as Walsh portrayed it.

The stadium issue came to a head when an over-capacity crowd in the Rams’ championship season of 1945 caused a temporary grandstand at League Park to collapse and break a limb of a paying fan. Why hadn’t the game been moved to Cleveland Stadium? The lease issue again was raised. “Besides,” Rams PR man Nate Wallack said later, Walsh “was stubborn.”

And he was shrewd too, as was Reeves. Both were adroit businessmen who probably could have found a way to move a game from League Park to Cleveland Stadium if they really had wanted to. Perhaps playing to a very large crowd would have eroded a running argument Reeves was waging with his fellow NFL owners: that Cleveland did not support his team, and hence he needed to move.

Not surprisingly, when the Rams remained at League Park while the far larger and newer Cleveland Stadium sat empty just miles away—the Rams, after all, had willingly signed the League Park lease—it did not help the team’s cause. John Dietrich of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, who was highly influential in local football circles, had covered the Rams through their entire tenure in Cleveland, and probably had extensive knowledge of the team’s inner workings, wrote just after the Rams had left town:

From the standpoint of public good will, it was a decisive blunder when the game with the Packers here last November—a feature that might have pulled 50,000 into Cleveland Stadium—was crammed into League Park. I believe the confusion of that afternoon cost the Rams thousands of patrons, permanently.

Instead of moving, Reeves—like Modell 50 years after him—told the media he wanted to stay where he was and fix the place up, “intimating” to the Chicago Daily Tribune in the immediate afterglow of the Rams’ championship-game victory over the Washington Redskins that he might expand League Park’s 23,000 capacity by 10,000 seats. This surely would have been problematic, however, with League Park being controlled by the Indians.

So why not give the Rams access to Cleveland Stadium? The city fathers were trying to maximize payback on an expensive 15-year-old stadium that was a terrible place to watch a football game and already was beginning to look like a white elephant.

Stadiums As a Political Football

So it should surprise no one that publicly owned stadiums were used as a political “football” even then. The City of Cleveland charged the Rams $10,000 to use Cleveland Stadium for the 1945 championship game (then had to make an unexpected outlay of additional labor and cost to clear the place of snow following a freak early-winter storm). This was a sweet deal for the Rams. In the 1940s the customary stadium payment in the NFL was 15 percent of the gross gate. After a take of $164,542 (which was a league record to that point), the city should have collected close to $25,000—two-and-a-half times what it actually pocketed.

And yet, not long after the title game—and continuing for decades to come—a rumor circulated that Cleveland had “gouged” the Rams for opportunistically high rent which further drove the team from the city. Walsh, in fact, owned up to a newspaper reporter on Christmas Eve 1945 that this claim had all been “just a little joke.”

A few weeks later, civic officials and Rams fans in Cleveland still were not laughing when the Rams packed up and moved to the West Coast.

It only goes to prove a point that apparently has been true for some time: It’s okay to accept the business and financial claims of professional sports owners at face value. Except when their lips are moving.